Part 3: Revolution, or How to Bitch About Taxes While Owning People (1700s–1780s)

By the 1700s, the colonies are a sprawling patchwork of tobacco fields, fishing villages, and sanctimonious hamlets, all simmering under Britain’s increasingly sweaty palm. They’ve carved out a decent hustle—land to spare, trade to hustle—but the crown’s starting to treat them like an ATM with an attitude problem. The trouble kicks off with the French and Indian War, a 1754–1763 brawl about who gets to chop down the most trees in the Ohio Valley. It’s the local leg of the Seven Years’ War, a global slugfest where Britain and France duke it out. The colonies pitch in—militias, supplies, a young George Washington botching his first command at Fort Necessity—while the Iroquois and other tribes pick sides or get steamrolled. Britain wins, snags Canada, and hands the colonists the bill, setting the stage for a tax tantrum that’ll echo for centuries.

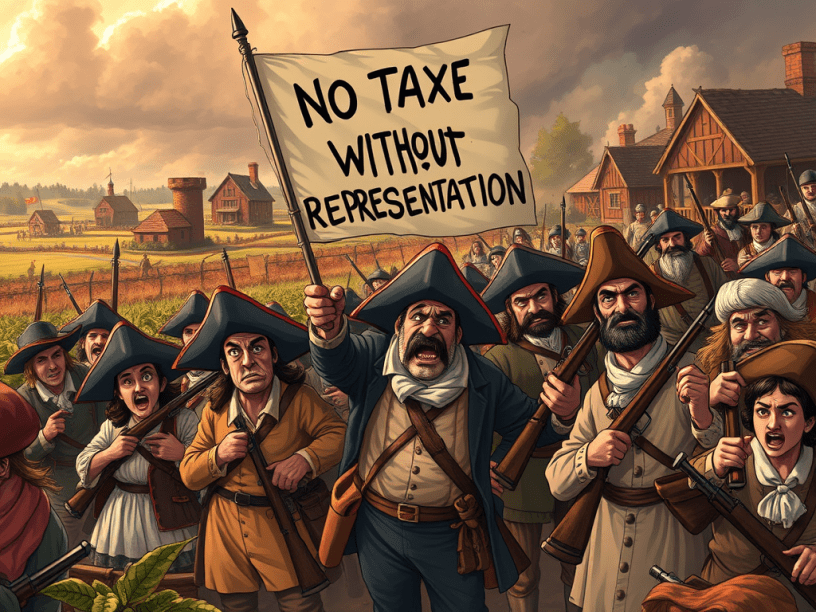

Fresh off that victory, Britain’s drowning in debt—wars aren’t cheap, and neither are redcoats—so they turn to the colonies with a grab bag of cash grabs. The Sugar Act of 1764 tweaks molasses duties, annoying rum distillers but not quite sparking a riot. Then comes the Stamp Act in 1765, a real ball breaker: every legal document, newspaper, even playing card needs a tax stamp, hitting lawyers, printers, and tavern gamblers alike. It’s not the cost—pennies, really—it’s the principle: “No taxation without representation,” cries Boston’s Samuel Adams, a brewer who’d rather torch his barrels than pay a tariff, though he’s got no qualms about slaves pouring his ale. Protests erupt—mobs tar-and-feather tax collectors, merchants boycott British goods, and the Sons of Liberty turn harassment into a patriotic art form. Parliament blinks, repeals it in 1766, but doubles down with the Townshend Acts, taxing glass, paint, and tea, proving they’ve learned nothing except how to poke the bear in a different spot.

The pot’s simmering now, and Boston’s the hot spot. In 1770, a snowball fight turns deadly—the Boston Massacre—when redcoats fire into a crowd, killing five, including Crispus Attucks, a Black sailor whose blood stains the road to a liberty he’ll never taste. Britain’s response is the Intolerable Acts of 1774, closing Boston’s port and quartering troops in homes after the 1773 Tea Party, where patriots in Mohawk drag dump a million bucks’ worth of tea into the harbor—not a bad night’s work for a costume party. The First Continental Congress convenes, a gaggle of wigged landlords in silk stockings whining about rights while their slaves polish the silverware back home. Then, in 1775, it blows open at Lexington and Concord: farmers with muskets face off against British regulars, and the “shot heard ‘round the world” turns the tax gripes into a full-on war.

Washington takes charge—a Virginia planter with wooden teeth and a knack for losing gracefully—leading a ragtag army through a slog of defeats and desperation. Valley Forge in 1777 is the low point: soldiers starve and shiver while Congress dithers over funds. But 1776 brings a bright spot: Thomas Jefferson, owner of 600 souls (including his own kids), pens the Declaration of Independence. “All men are created equal,” he writes, a line so dripping with irony it could fertilize his fields. It’s a defiant jab at King George III—too busy losing wars and his marbles to care—and a promise that stops at white, male, landed doors. The war grinds on—Bunker Hill, Saratoga—until France, smelling British blood, joins in 1778. By 1781, Cornwallis is cornered at Yorktown, pinned by Washington’s scrappers and French ships, and surrenders with a shrug. The 1783 Treaty of Paris seals it: Britain’s out, America’s born, and the real mess begins.

Freedom’s the prize, but it’s a limited-time offer. Slaves—20% of the population—get nothing; Virginia’s got more in chains than Massachusetts has taxpayers. Women sew the flags, not the laws. The Iroquois, shredded by the war’s crossfire, lose lands to “victory” either way. Working stiffs—dockhands, farmers—cheer the redcoats’ exit but stay under the same old thumbs. The Founding Fathers—Washington, Adams, Jefferson, Franklin—forge the Constitution in 1787, a slick compromise of three branches and checks, with a Bill of Rights tacked on later to hush the rabble. But slavery’s the elephant in the room: the three-fifths clause boosts Southern power without freeing a soul, and a fugitive slave law keeps the chains rattling. Washington steps up as president in 1789, a reluctant king for a republic already dodging its own ideals.

This isn’t the pristine “dawn of democracy” you were sold—it’s a revolt of the haves against the have-mores, wrapped in noble rhetoric and riddled with holes. The French and Indian War left a tab, the Stamp Act lit the fuse, and the patriots turned a tax beef into a nation.