At approximately the hour when most normal people are asleep and only the raccoons and crackheads are awake, the United States of America announced it had captured the sitting president of Venezuela in a large-scale strike / raid in Caracas and flown him out of the country to face U.S. charges.

And because we are who we are, we didn’t stop there. The President also said—out loud, with cameras rolling—that the U.S. is going to “run” Venezuela for now and, in the same breath, talked about tapping Venezuela’s oil wealth like this is a Home Depot project and the only thing missing is a YouTube tutorial called How To Rewire A Sovereign Nation (Beginner Friendly).

If you’re wondering whether this is “normal,” the answer is: it is perfectly normal for the United States in the same way it’s normal for a golden retriever to eat a couch. We do not merely have impulses; we are the impulse.

The sales pitch is already in circulation: narco-terrorism, the war on drugs, a fugitive strongman, justice, stability, freedom, etc. Maduro is headed toward New York on serious U.S. charges, as framed by the administration and covered as such. The operation has a name—because all American violence must have branding—and it has the familiar supporting cast: elite units, intelligence support, aircraft, “precision,” and the kind of cinematic adjectives that make Americans feel warm and safe about things that usually end with memorials and congressional hearings.

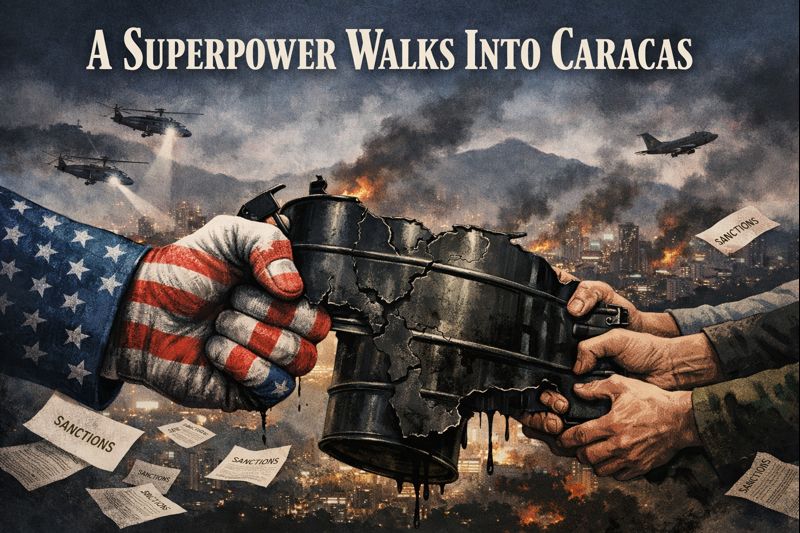

And then there’s the oil. Always the oil.

Because this is the part where the mask isn’t “off.” It’s not even hanging from one ear. It’s been set gently on a table, smoothed with the fingertips, and replaced with a laminated sign that reads: WE ARE HERE FOR THE OIL.

The America that can’t quit the “Liberate” button

The U.S. relationship with Venezuela has been a long, ugly scrapbook of sanctions, pressure campaigns, half-diplomacy, full hypocrisy, and periodic moral speeches delivered from behind the steering wheel of a moving tank.

Congressional Research Service summaries lay out the sanctioned labyrinth: targeted sanctions going back years, then broader financial/sector sanctions as repression increased, then limited relief attempts tied to elections, then the re-tightening when the elections went the “wrong” way (or at least the disputed way). That same overview sketches the political reality we keep stepping over like it’s a rake in a cartoon: Venezuela’s 2024 election was widely disputed, the opposition’s candidate (Edmundo González) is described as having had results indicating he won, and the post-election period included repression, exile, and an opposition leader (María Corina Machado) in hiding.

So yes: Venezuela is a mess. But it’s also the kind of mess that, in the American imagination, always looks like a vending machine that ate our dollar. We don’t ask what the country needs; we bang the glass, shake the machine, and then send in a SEAL team to “restore functionality.”

And it’s not like there wasn’t already an escalatory ladder. Just days ago, Treasury was still doing what Treasury does: sanctioning oil traders and tankers, talking about “shadow fleets,” “sanctions evasion,” and how oil exports provide resources to Maduro’s regime. There’s your prequel: paperwork, blacklists, and press releases. Then, suddenly: bombs, raids, and a head of state imprisoned on a warship.

Somewhere in Washington a policy intern is updating the flowchart:

Targeted sanctions → sectoral sanctions → licenses → license lapses → shadow fleet → “large-scale strike.”

“War on drugs” meets “war for heavy crude”

Here’s what makes this particular shitstorm so… American. We managed to merge three national obsessions into one cinematic event:

- The war on drugs (a decades-long performance piece where the drugs always win).

- Regime change (our most consistent export besides streaming content).

- Oil (the eternal subplot that becomes the plot whenever the cameras are on).

The administration’s framing leans hard on the narco-terror angle—Maduro as a criminal kingpin, a “regime” flooding the U.S. with poison, etc.—which matches the public justification you’re seeing in official messaging and coverage. But the President also made a point of telling the world that American oil companies will spend billions rebuilding Venezuela’s oil infrastructure, and that the U.S. will have a presence tied to oil.

Reuters notes analysts warning that rebuilding Venezuela’s oil sector isn’t a quick flip; it’s a years-long rebuild requiring tens of billions—meaning this is not a “quick justice mission.” It’s a long-term entanglement with hard hats and security perimeters.

And if you listen closely, you can hear the old American hymn:

We came to help, we stayed to manage, we left eventually, and everyone got a commemorative coin except the people who lived there.

The legal questions are not a footnote — they’re the whole page

One of the more revealing details is that reporting indicates Congress was not informed beforehand, prompting immediate blowback and questions about authorization. This is the part where the bipartisan concern starts sounding less like principle and more like professionals annoyed that someone redecorated the office without sending a calendar invite.

Because think about what just happened in plain English: the U.S. conducted strikes inside a sovereign country and seized its leader. That’s not “a policy shift.” That’s a new chapter in the regional memory that begins with, “Remember when the Yankees came back?”

Even defenders can’t resist reaching for the old precedent: the 1989 capture of Manuel Noriega in Panama gets invoked as the historical analog. Which is a little like saying, “Relax, we’ve done this before,” as if that’s comforting and not, in fact, the precise reason everyone is staring at us like we’re the guy at the bar who keeps mentioning he “used to skate.”

The world’s reaction: you can’t “stabilize” a country you just hit with a sledgehammer

International reaction has been swift and loud, with leaders and institutions condemning the intervention and raising international-law concerns. Venezuela has sought action at the UN level, and UN leadership has expressed alarm about escalation.

This is where America’s “freedom” narrative collides with the very old, very reasonable fear that the U.S. has just normalized a new standard: If we don’t like you, we can come get you. And yes, lots of people didn’t like Maduro. That’s not the point. The point is that the precedent doesn’t come with a “for dictators only” safety lock. Precedents travel.

Meanwhile, inside Venezuela, the picture is chaotic: protests, celebrations, uncertainty about succession, officials denouncing the operation, and a country that has already been battered by years of economic collapse and political repression now being told it’s getting a “temporary manager” with an American flag on his lapel.

America loves the phrase “power vacuum,” mostly because we treat it like a household problem: just plug in another power source and it’ll be fine. But states don’t behave like living rooms. The real vacuum is usually filled by whichever armed actors are already embedded—military commanders, security services, money networks—people who don’t vanish because a single man gets flown out at dawn. Analysts are already warning that what comes next depends on those power brokers and how they react.

This didn’t start this week. It’s been building like a bad headache.

The current blow-up sits atop a long-running escalation that mixed sanctions, migration pressure, hostage politics, and oil licensing.

Remember: in July 2025, Venezuela released 10 jailed U.S. citizens/permanent residents in a swap tied to Venezuelans deported and held abroad—part of an ugly diplomacy-by-hostage pipeline that’s become a recurring feature of the relationship. In March 2025, Reuters reported the U.S. had formally identified wrongfully detained Americans in Venezuela, highlighting how the detention issue became an ongoing lever.

Layer that onto the sanctions story—licenses granted, licenses lapsed, oil pressure, “shadow fleets,” tanker designations—and you get a pressure cooker.

Then, on January 3, 2026, it whistles. Loud.

The most American part: we’re already discussing the oil contracts like it’s a refinance

Within hours of the capture, the conversation turned into a kind of deranged investor call. Which U.S. oil companies will return? How fast can production be restored? How long will it take to rebuild decayed infrastructure?

America can’t fix a bridge in Pittsburgh without a decade of studies and a lawsuit from a salamander, but we’re apparently ready to administer another country and rebuild an entire oil sector because we saw an opening and the word “reserves” lit up in our eyes like a slot machine.

And it’s not even that Venezuela’s oil isn’t real—Venezuela’s reserves are famously huge. The problem is the American habit of confusing resources with governance, as if crude in the ground is the same thing as legitimacy on the streets.

So what now?

Here’s the honest version, minus the patriotic soundtrack:

- If the U.S. stays—militarily, administratively, “until demands are met,” as framed in the reporting—then you’re looking at occupation dynamics, insurgency risk, sabotage risk, and a permanent recruiting poster for every anti-U.S. actor in the hemisphere.

- If the U.S. leaves quickly, you risk the “mission accomplished” sequel where the strongest remaining internal faction consolidates power and we declare victory anyway, because America loves declaring victory.

- If the U.S. tries to hand off power to a transition, it’s going to collide with the reality that Venezuelan institutions have been bent for years, opposition has been repressed, and legitimacy isn’t something you can airdrop with MREs.

And on the American side, you can already feel the domestic fight warming up: legality, War Powers, “briefings,” “intel,” “authorization,” and the usual Washington sport of arguing over process only after the plane has taken off and the engine is on fire.

The darkest joke here is that the people who will pay first aren’t the speechmakers. They’re Venezuelans trying to get to work during a “liberation,” and American service members who didn’t sign up to become the security detail for an oil rehab project.

We’ve entered the phase where everything is being sold as both a moral crusade and a business plan. That combination—righteousness + revenue—is how America gets itself into decade-long tragedies while insisting it’s doing the world a favor.